Salmon Science

Integral to the Northwest

Salmon are environmentally and culturally significant.

Salmon play important roles in the cultures and histories of people who have lived here for thousands of years.

These amazing fish make extraordinary migrations from streams to the ocean, then back again to spawn.

Coho salmon spend their first year in freshwater, then travel to the ocean in the spring, where they feed and grow for the next 16-20 months. It is at this stage that they are known as smolts, and are identifiable by their silver color. After their first summer at sea, some males that have reached sexual maturity early (known as jacks) return to freshwater. The rest of the fish return to freshwater at about three years old to spawn. Coho are found throughout the entire watershed.

Chinook also are present in Johnson Creek, but they are rarely seen anywhere except the lowest reaches.

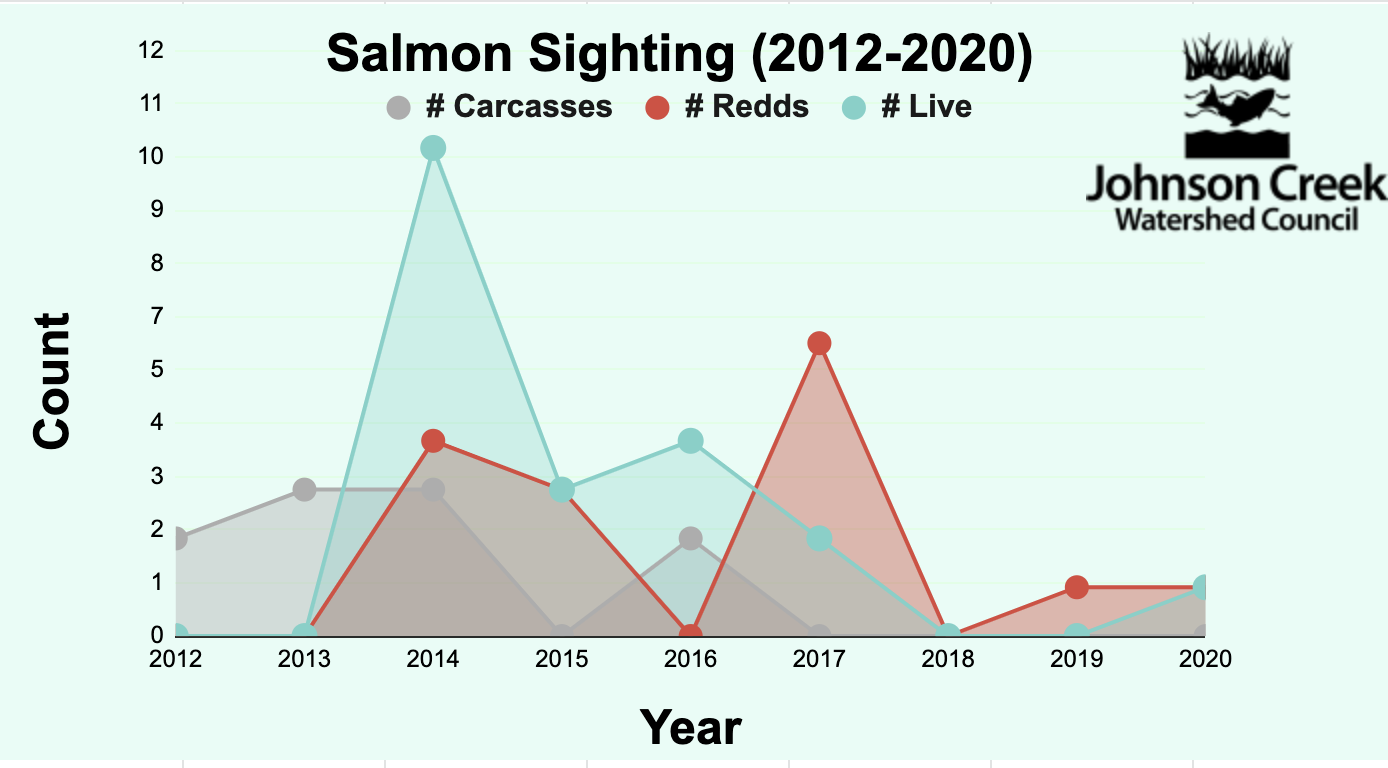

Since 2011, JCWC volunteers have been surveying the creek for coho and Chinook, gathering data that supports our restoration efforts.

Life History

Coho salmon are anadromous. This term refers to fish that are born in fresh water, travel to the ocean to live their adult lives, and return to fresh water to spawn. In order to undergo this major change in conditions, the fishes’ bodies change in appearance and structure…all so they can reach their natal streams. Incredibly, salmon find their way to the same location where they hatched years before – very impressive! Scientists are unsure how salmon navigate back to their “home,” but it has been suggested that they use the earth’s magnetic field to orient themselves.

Most salmon species, including coho, expend their last bit of energy spawning. Their carcasses remain in the stream to feed other animals and plants, one of the ways they are vital to Pacific Northwest ecosystems: they bring nutrients far upstream from the ocean. (When carcasses are removed from Johnson Creek by our volunteer surveyors, JCWC staff return the carcasses to the creek after processing them.)

Once thriving populations

Salmon populations in Johnson Creek have changed dramatically in the last century. Historical Johnson Creek coho runs once numbered as many as 5,000 adult fish each year, but as the area around Johnson Creek became more heavily developed, coho runs declined rapidly. Chinook salmon similarly suffered–by 2000, Lower Colombia River coho and Chinook were both listed as threatened. Only a handful of each are spotted in Johnson Creek annually.

To better understand salmon in Johnson Creek, JCWC began working with Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife (ODFW) to design a community science program in which volunteers could help gather salmon data. We train volunteers using ODFW protocols, thus expanding their surveys to cover far more ground.

Over 50 volunteers have performed salmon spawning surveys. This volunteer effort has given us a much better picture of salmon activity, which helps inform our restoration projects.

Methodology

Each year, we select several mile-long reaches to be surveyed by volunteers. Some reaches are surveyed every year, while others change from year to year. Volunteers are trained in early fall by fish biologists from ODFW, who teach them how to identify coho vs. Chinook fish and redds (spawning nests).

Volunteers are assigned mile-long reaches and walk those reaches in pairs, with each reach being surveyed each weekend through the fall months when both species spawn. Surveyors photograph any live fish or redds they encounter, taking notes and reporting all sightings. Fish carcasses found during surveys are transported to the JCWC office, where staff determine age, sex, and spawning activity of the salmon when possible.