Dragonfly Science

Water quality indicators

Dragonflies and damselflies offer important clues about ecosystem health.

Dragonflies are predatory, capturing other insects in mid-flight!

By monitoring dragonflies and damselflies (collectively known as Odonates) every year, we can create a picture of the changes in composition and seasonality of local and migratory populations.

We began surveying dragonflies and damselflies in our watershed in 2016, and we’ have continued each year’ve added additional sites as our community scientist interest has grown. In fact, we’ve learned that the Johnson Creek Watershed is home to three of the five main species of migratory dragonflies in North America: the common green darner, the variegated meadowhawk, and the black saddlebag.

What we’ve discovered together –

Climate change is affecting dragonflies and damselflies.

23

Species

4

Sites

1000+

Observations

Odonate surveys can provide important information about changes in habitat quality, as well as impacts of climate change.

Life History

When talking about dragonflies and damselflies, we often just say “dragonflies” as shorthand. But this leaves out the poor damselflies, which are closely related. Dragonflies and damselflies are a bit like cousins, and if you want to talk about both, you can use the word “odonate.”

Odontos is the Greek word for tooth. Odonates are carnivorous as nymphs and adults, and the nymphs are characterized by toothed mandibles (jaws) at the end of a long, extendable mouth part.

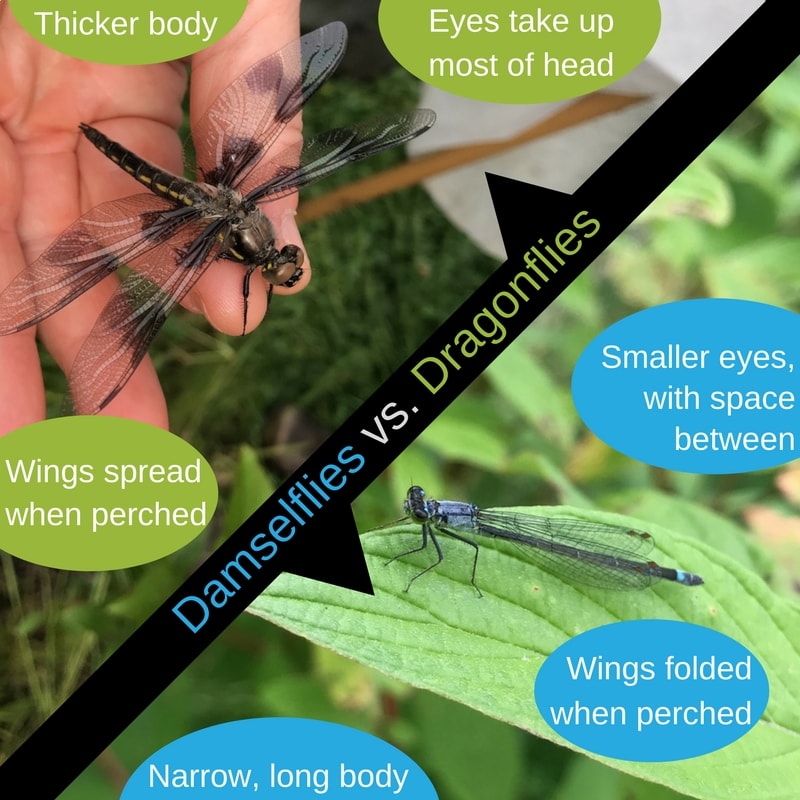

It’s actually pretty easy to tell the two apart! Just look at three key features- their eyes, body, and wings.

Dragonflies & Damselflies

The goal of these surveys is to document:

- Diversity, or the number of species found in the watershed

- Abundance, or how many of each species might live in the watershed.

- Timing of species’ occurrence: When do adult dragonflies and damselflies first appear in our watershed? How might this compare with other local areas, or with other years?

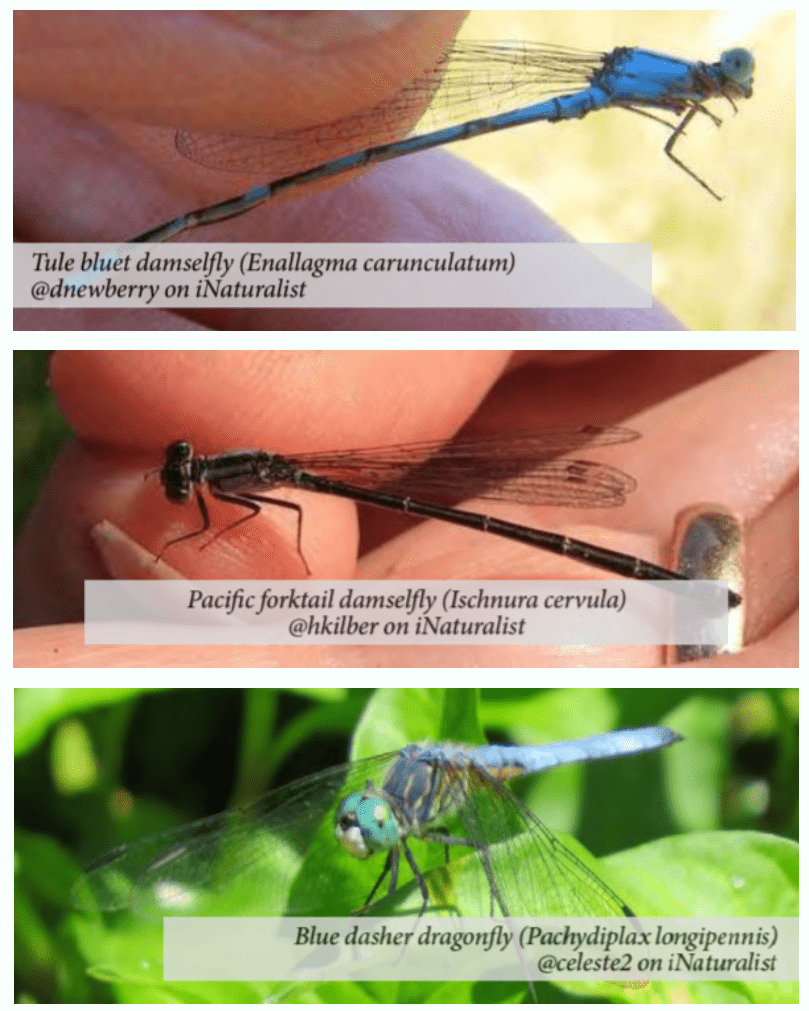

The most common species found throughout Johnson Creek are the tule bluet damselfly (Enallagma carunculatum), the Pacific forktail damselfly (Ischnura cervula), and the blue dasher dragonfly (Pachydiplax longipennis).

Methodology

Volunteers conduct surveys about every two weeks. Odonate activity fluctuates a lot with temperature, cloud cover, wind, and more, so the timing of surveys may vary based on when conditions are optimal. Surveyors are armed with a net, hand lens, dichotomous key for identifying odonates to the family level, and a field guide to identify them to the species level. Volunteer teams walk transects along a water’s edge at each site, taking photos and netting individuals when possible. They record species, abundance, genders, and reproductive stage.

Early in the season, our teams are especially careful to avoid netting newly-emerged odonates that have delicate wings. (You can tell an odonate emerged recently because their wings have a soap-bubble appearance.) All of our data is reported on iNaturalist.

Survey methods were developed by C. Zee Searles Mazzacano of CASM Environmental. Zee is our entomologist extraordinaire and scientific advisor on this project.