After many years of running the “What’s That Weed?” column, it feels like time to take a more positive look at the plant world! The Pacific northwest is home to a huge diversity of really cool native species (many of which have shown up as replacements for weeds that have been featured here). Let’s go botanize!

Featured native: Poison oak (Toxicodendron diversilobum)

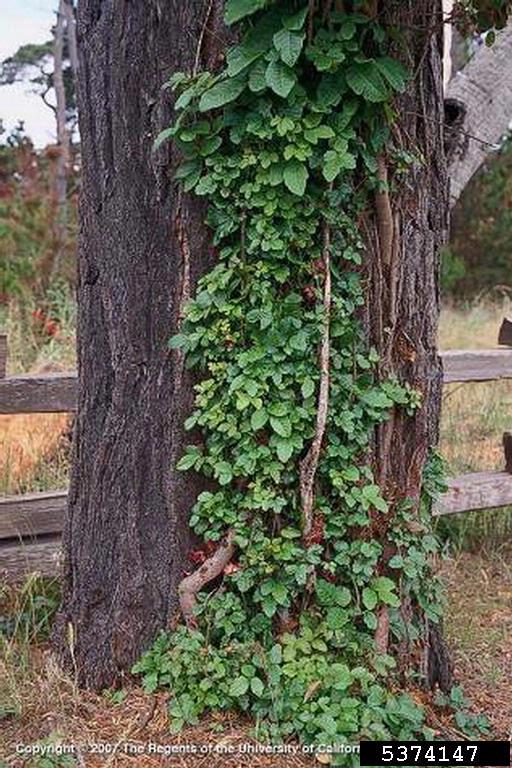

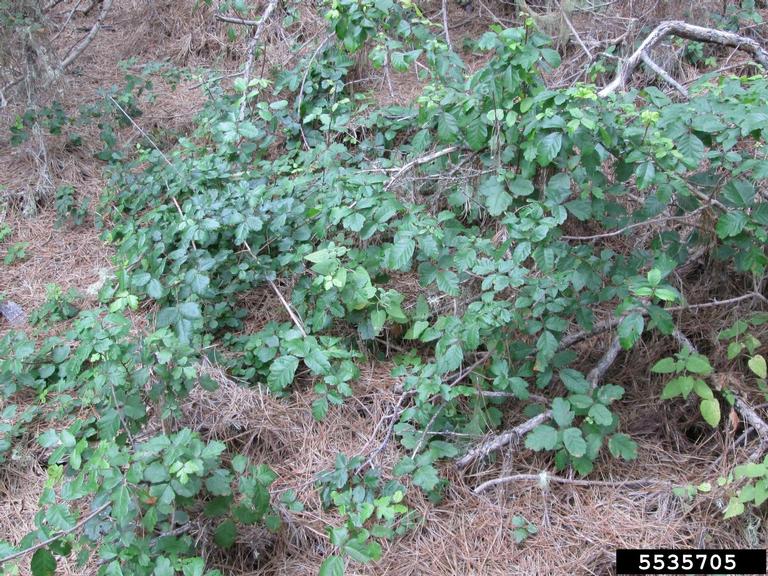

What?!? Opening a column on native plants with poison oak? Well, why not? Western poison oak is a native, if less than beloved (by humans), species. Not an oak at all, it is a member of the cashew family (Anadcardiaceae) that can grow in a wide array of habitats…and habits. It typically shows up as shrubby thickets up to 2 m (6 1/2′) tall when in full sun, while in shady areas it often acts more like a spreading (or even climbing) vine/ground cover. Its glossy, irregularly-lobed leaves emerge a glossy mahogany in late winter (February-early March), turning a deep, often shiny green for most of the growing season before going red again in the fall prior to leaf drop. Famously, its compound leaves generally feature three leaflets (whence the rhyme: “leaves of three, let it be”), up to around 12 cm (4 3/4″) long, with lobes similar to those of the Oregon white oak, hence the “oak” part of its common name. The “poison” part is due to the presence of urushiol, a mixture of closely-related organic compounds that can cause an itchy rash if left in contact with skin (and is REALLY bad news if inhaled, e.g., as smoke from burning poison oak). About 85 or 90% of people have an allergic reaction, which usually shows up 24-72 hours after exposure. Direct contact isn’t the only way to get exposed: urushiol will transfer from clothing, pets who come in contact with the plant, or even objects such as garden tools or errant baseballs. Urushiol is in all parts of the plant, at all times of year, so even winter contact with bare branches can result in a reaction if the offending stuff isn’t removed. Parenthetically, all members of the cashew family contain urushiol, including cashew nuts; those “raw” cashews you’ve seen at the store have actually been steamed or boiled in the shell to remove the urushiol.

Poison oak’s small (0.5-cm, or roughly 1/4″), greenish-white flowers are star-shaped and appear in diffuse clusters, emerging anywhere from late March to June. Male and female flowers look very similar to one another, but are borne on separate plants (“dioecius” is the botanical term for this arrangement). Female flowers give rise to small, round fruits, also greenish-white, that last through fall and into winter. Seeds from these fruits are one means by which poison oak can reproduce; it can also spread vegetatively by putting up new sprouts from underground rhizomes or from its root crown.

While many people take a dim view of this plant, it is quite important ecologically; wildlife do not share humans’ sensitivity to the urushiol. Many birds, including towhees, robins, and grossbeaks, eat its berries, as well as the insects that inhabit poison oak thickets. Deer and other animals browse on its leaves, and small mammals may take shelter in its dense growth.

Adding poison oak to landscaping is probably not of interest, unless you’re trying to keep people out (in which case a safer bet would be to just put up a warning sign saying it’s there, but not actually plant it)! But, if you should chance across it while you’re out and about, enjoy its glossy foliage (from a respectful distance), admire its adaptability, and know that it’s serving an important function for birds and mammals. (Just don’t let your dog chase them in there!)